The council, the three judges said, was dealing with its own people “like with a magic spell whose wand is uncertain”.

“And this has created a spiral of confusion and uncertainty and has left some (law graduates) languishing in the streets without a chance of (of enrolment to the bar), Judges H Wolayo, Lydia Mugambe and Musa Ssekaana said.

The matter before them was that of Tony Katungi who studied his law degree at the Ugandan Christian University and then went to Kenya where he completed his bar course training and was admitted to the Bar as an advocate.

He returned home and applied to the Council to be similarly admitted.

But, he was told, he had to do a further year of “supervised practice” at chambers chosen by the council.

Katungi went to court, arguing that this was in bad faith.

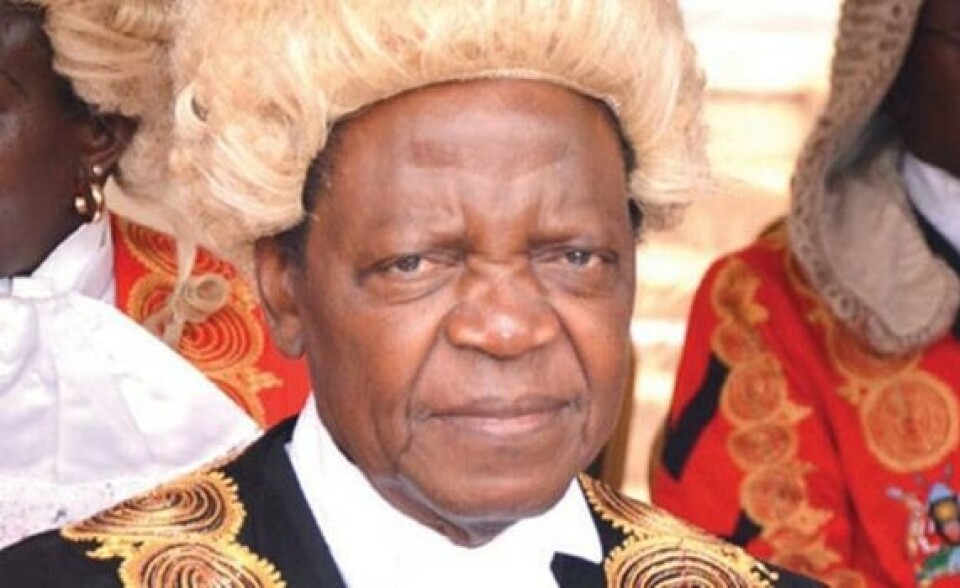

Council chairperson, Justice Remmy Kasule, insisted that Katungi needed to be “vetted” which could only be done through surveillance and supervision “to determine whether his work satisfied or did not satisfy professional standards”.

Kasule said this was the law.

But the judges said it was clear that the council had never considered Katungi’s further education and training in Kenya.

And, they said, the council had misinterpreted the law, saying this was for “legal practitioners” - people without law degrees but enrolled as legal practitioners by virtue of their legal related work experience such as clerks, paralegals and police officers.

They also lamented the lack of regulations which would set out how law graduates would be deemed to have practised for the minimum period of one year.

“We have not come across any regulations…the council have arrogated to themselves powers to consider applications on a case by case basis which is very wrong and must stop.

“It must enact these regulations so that students make well informed decisions when choosing where to study, with a sense of future certainty of where they can practise their profession. “

They said they recognised the important duty of the council to protect the legal professional from “quack lawyers with quack qualifications” who were infiltrating the profession.

But the objectives of the Act were to make access to the profession easier.

The East African Community Treaty also provided that partner states should take all steps to establish a common syllabus for the training lawyers, and common standards to be attained in examination.

Uganda was also a signatory to the East African Common Market Protocol, binding it to allow free movement of workers.

“In today’s world the Council needs to be alive to the fact that many Ugandans study law degrees in other countries not because they are intellectually incompetent but simply because they cannot be accommodated here.

“There is a need not to unfairly discriminate against these students in comparison to those who study in Uganda,” the judges said.