Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

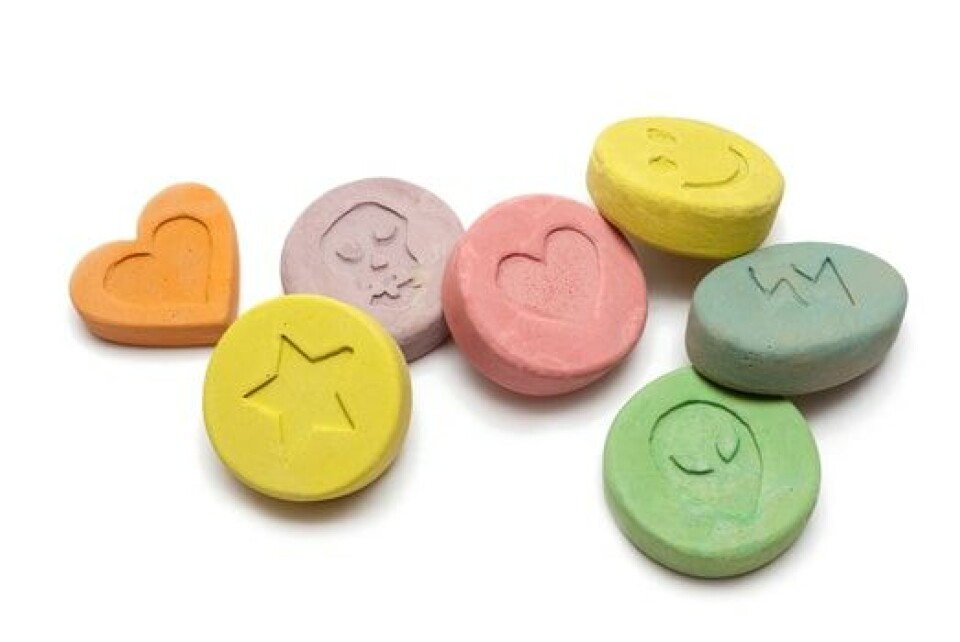

Party Drug Conundrum

A possible loophole in the law, which prohibits the possession of “club drug” Ecstasy, is in the spotlight in South Africa. Tania Broughton reports.

It’s a case which has seen two of the country’s top legal minds - Advocates Kemp J Kemp, SC, and Andrea Gabriel, SC - pitted against each other.

And, while for now it has only be argued in the high court in Durban - and a judgment is awaited - the legal attack will have to be finally resolved at Constitutional Court level.

The challengers are alleged drug dealers, a popular Durban bar owner, Greg Ayres, and Bulgarian national, Valeri Nicolov, who were “bust” with 600 000 Ecstasy tablets, said to be worth R85 million, in Middleburg in November 2014.

For now their case has been struck from the roll while courts consider their argument that the drug has never been lawfully outlawed. There is a lot at stake. Drug dealing in South Africa can carry penalties of up to 25 years in prison.

If they win, criminal charges will have to be withdrawn against them and others facing prosecution.

The issue the courts will have to pronounce on is, whether or not the Minister of Justice, when he outlawed the drug in 1999, was legally entitled to do so without referring the matter first to parliament.

It’s all about separation of powers.

In his argument, Kemp, for Ayres and Nicolov, said Ecstasy (or MDMA as it is referred to in the act), was not lawfully included in the schedules to the Act.

Hence, his client’s conduct was not criminal.

His argument is founded on the fact that, when the Act was passed in 1992, with parliamentary oversight, MDMA was not in the schedules of outlawed substances. It was only inserted by the (then) Minister in 1999 without parliamentary oversight.

“Criminalisation of substances had extreme consequences and compromise the constitutional rights of dignity, privacy, arrest, prosecution and punishment. The mere potential exposure to criminality and severe sentences is a matter which should belong firmly and exclusively to parliament with the checks and balances applicable to parliamentary law-making.”

“It matters not that the Minister’s motives may have been noble. The point is there has not been a constitutional valid criminalisation of it.”

Advocate Gabriel, for the Minister, pointed out that the challengers do not claim, at this stage, any rights violations. And they are silent on whether or not the drug should be banned.

Referring to similar “separation of powers” challenges, she said the Constitutional Court had ruled that it was permissible for parliament to delegate powers, especially when it involved rapid decision making and the decisions were within the framework of the Act.

She said in this matter, the Minister had only amended the schedule and not the Act.

“Parliament, when it passed the Act, made it clear what substances it considered undesirable and dangerous and itemised certain known drugs at the time.

“Since then we know South Africa is on the ‘drug route’ and we have ratified three international treaties in the ‘war against drugs’ which were binding in terms of the constitution.”

“It is impossible in a modern state to expect parliament to legislate for every eventuality.”

To read more South Africa focused news and analysis, click here.