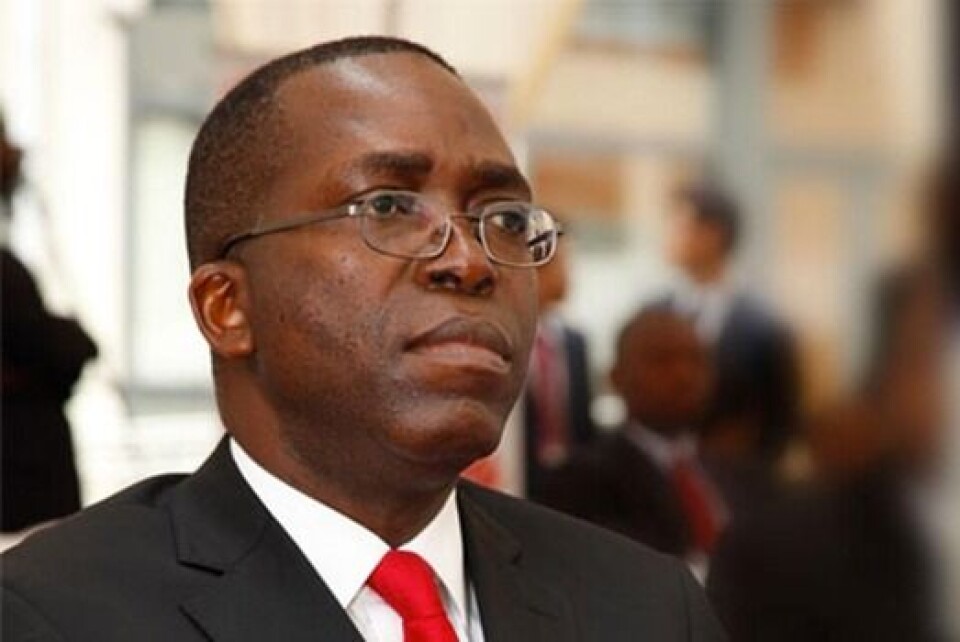

In 2020 the Inspectorate General of Finances (IGF) accused Mponyo of embezzling $205 million intended for the Bukanga-Lonzo Agro-Industrial Park project which was supposed to help solve the country’s food crisis. In his plea on 8 November 2021, Mponyo's lawyer, Raphael Nyabirungu, listed a dozen violations of the procedure before the Constitutional Court and presented his client as innocent, saying as he was no longer prime minister he could not be prosecuted for offences committed when he was head of government.

The lawyer bases his argument on numerous articles of the Constitution and the Organic Law on the Constitutional Court. Article 163 of the Constitution, for example, stipulates that the Constitutional Court can only judge a president and a prime minister who are in office. Nyabirungu also cited Articles 101, 102, 103 and 105 of the organic law, which do not give the Constitutional Court the power to refer cases to the presidents of the National Assembly and the Senate in order to judge a member of parliament, but only a prime minister and a president in office.

The former prime minister is currently a senator. He therefore enjoys the immunities granted to former heads of state under articles 163 and 164 of the Constitution, as well as the immunities granted to members of parliament during their term of office, except in cases where they are caught in the act of a crime.

Civil society is concerned that the former prime minister may be able to escape justice, and Rule of the Law in Action rejects Nyabirungu’s arguments outright. "This is an aberrant line of reasoning because it is not based on any logic or scientific foundation. The logic is that we cannot have a legal system that does not condemn a person who steals,” pointed out Oscar Mubiayi, coordinator of the association.

Professor Lozolo Bambi, a constitutional scholar and former member of the Constitutional Court, agrees, asserting that the Constitutional Court is the competent criminal court to try the prime minister – whether former or current – for offences committed during or in connection with the exercise of his duties.

In his view, the reasoning developed in the Constitutional Court's first ruling last November (which led the court to declare itself incompetent to try the former prime minister), disregarded one of the fundamental principles of criminal law, namely that of crystallisation when one goes back to the time when the acts were committed and reconstructs what happened at that time.

Cases of former or current high-ranking State officials seeking immunity from prosecution are common in Africa. One such case involves Mozambique's president, Filipe Nyusi, who is asking the High Court in London to block allegations that he accepted illegal payments as part of the country's lawsuit against Credit Suisse and others in the $2 billion “tuna bonds” scandal.

In 2014, civil society organisations from 19 African countries appealed to the African Union to reject immunity for heads of state and government before the African Court of Justice and Human Rights, but their pleas were ignored. In a controversial decision, the African Union decided to specifically exempt senior government officials from prosecution by the regional human rights court.

To join Africa Legal's mailing list please click here