Judge Musa Ssekaana had some harsh words for the Centre for Constitutional Governance, before “striking out” its application for “incompetence”.

“The applicant has not cited any infringement of any right or freedom guaranteed under the constitution as the basis of filing this application,” he said.

“The applicant should have filed an application for judicial review of the decision (to introduce e-passports rather than filing an application for enforcement of rights where no single right is mentioned or the article of the constitution is cited,” he said.

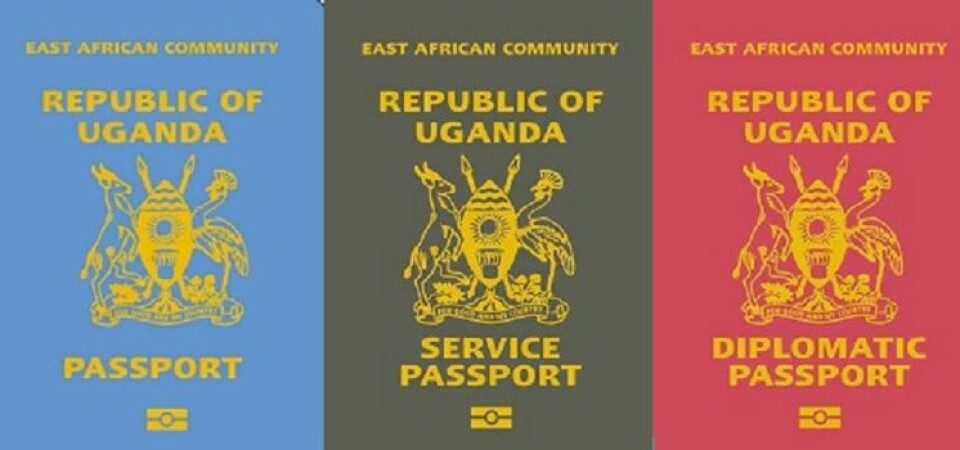

The roll-out of the e-passports - which have an electronic chip encoded with the holders personal information - was sanctioned by EAC states (Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi) in March 2016.

But, last year the centre, along with local attorney Michael Aboneka cried foul and lodged an application “in the public interest” for an “enforcement of rights” asking for an order that the Ministry of Home Affairs be “restrained from recalling all old passports and the issuing of new ones”.

They alleged there was no local law allowing this - only EAC law, that it violated the principle of sovereignty and was a “breach of contract” with the people of Uganda.

Further, they argued, citizens had not been sensitized to the “new venture”. This had left them “to the Mercy of God”.

But, the government respondents said passports were the property of the government. The issue of e-passports was lawful and was required to fulfil the EAC mandate “to facilitate the free movement of goods, persons and labour to accelerate economic growth and development” in the region.

It was also in compliance with international conventions that travel documents must have special biometric features to avert the risk of forgery and duplication.

Judge Ssekaana, in his recent ruling, said:“ In order to proceed or bring actions under Article 50 of the constitution, the matter must relate directly to fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed under the constitution.”

“This court has perused the entire application and has not come across any right or freedom which the applicant alleges was violated or was threatened to be violated.

“Their submissions were confused and unpolished,” he said.

Commenting on the issue of “public interest litigation”, Judge Ssekaana said these cases should be restricted to “gross violation of fundamental rights or acts which shock judicial conscience” and lodged to remedy hardships and miseries of the needy and the underdog.

“It is true that public interest litigation has been abused and is increasingly used by advocates for publicity and or seeking prominence in the legal profession - and it is now ‘publicity litigation’.

“The courts should be circumspect in recognising public interest standing and the judicial officer must determine whether the applicant is a genuine public interest litigant and is not acting malafide for personal gain, private profit or for political or other oblique considerations.”